Reflecting on our bloating wardrobes

- Vivian Shi

- Jun 21, 2024

- 10 min read

Part 1 of the Spotlight Series on Textile Repair & Waste Reduction

Grow at all (hidden) costs?

Textiles and clothing are undoubtedly an essential part of our everyday lives. Compared to just a few generations ago, we now have an (over)abundance of choices for clothing. Between 2000 and 2015, clothing production has approximately doubled globally – predominantly driven by Fast Fashion business models that are optimized to sell more, for lower prices and at lower quality. A recent research showed that global clothing production is now outstripping GDP growth.

At the same time, we are wearing each garment far less often than we used to. The global average rate of clothing utilization (the number of wears before disposal) has decreased continuously since 2000. This trend reflects the dual shift in product durability and our attitude towards shopping. When I was growing up, shopping for new clothes was an occasion and each piece was to be treasured for years. By the time I discovered the OGs of Fast Fashion like H&M and Zara, new clothes were so ubiquitous, cheap, and flimsy that they had become disposable commodities. It is hardly surprising that what followed was less thoughts, time, and money spent on maintaining and repairing these inherently low-value items.

(Left) Clothing sales doubled globally between 2000 and 2015, meanwhile clothing utilization declined by more than 36% according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (Right) Recent research led by the Green Alliance confirmed that global clothing production is now outstripping GDP growth, bouncing back from a drop from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The vicious cycle of ‘buying more – caring less – disposing more’ is driving a frankly mind-boggling level of waste and pollution. In terms of absolute quantities, the world already has enough clothes to dress the next 6 generations! On climate change alone, the fashion industry is contributing 4% to 10% of the global emissions depending on the source – this is comparable with the aviation sector and heavy industries such as steel or cement production.

Additionally, human rights issues in the complex, opaque, and global textile supply chain still trouble the sector. The ultra-low prices and fast turnarounds of micro seasons/collections are largely rendered possible by exploitative labor practices. The tragic Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013 brought this issue to the foreground. Since then, brands, NGOs and regulators have been working on improving supply chain transparency and preventing/reducing risks of human rights abuse. Still, findings from the 2023 Global Slavery Index report warns that a total of US$147.9 billion worth of garments and US$12.7 billion worth of textiles are still at risk of being produced by forced labor and are imported annually by G20 countries. If you’d like to get a sense of the practical challenges on the ground, the CBC’s recent follow-up investigation on the conditions of Fast Fashion workers 10 years after the Rana Plaza tragedy is highly worth a listen.

The hard truth is, as long as the vicious cycle of overproduction and overconsumption prevails, we continue to pass the real cost of fashion onto other people – those under exploitation right now, and those to come in future generations.

The Confessions of a Shopaholic is one of my guilty pleasures, but no – shopping doesn’t make the world better.

The time for (Re-) action is now

As with most sustainability-related debates, there is tension between advocating for personal lifestyle changes and system-level actions. However, since we are all a part of this broken system, I believe that it takes collective action to arrive at the solutions.

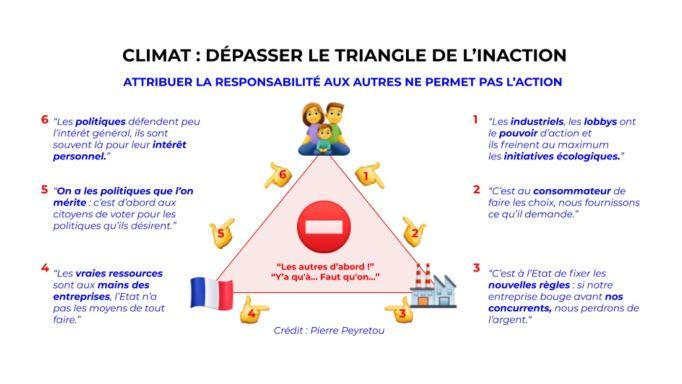

Caution: the triangle of inaction ahead! Image: The Climate Fresk

From our personal corner of the inaction triangle, we can act within our power by becoming more informed and conscious of our purchasing decisions; and in doing so, signalling to industries and governments the kinds of changes we desire. A great place to start is to learn and apply the 7Rs of Fashion, as highlighted by Fashion Takes Action (FTA) - the leading nonprofit organization in Canada on this subject. For anyone wanting to learn about sustainability, ethics, and material circularity in the fashion system, the FTA’s resource page is a treasure trove of bite-sized and practical information!

For every inaction, there is a Re-action ;)

Before elaborating on other ways to shrink our fashion footprints, it's important to recognize that any meaningful action towards sustainability, from both brands and individuals, must start with Reduction.

If the fashion industry is seriously committed to a 1.5°C decarbonization pathway (i.e. urgently and drastically limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels), then its absolute carbon footprint needs to be reduced by at least 50% to 60% by 2030 compared to 2018 levels. That is a steep drop that cannot be achieved through just material innovations or recycling, not least when clothes are being made, bought, and thrown away at the current rate.

In 2022, the Textile 2030 Initiative (representing 62% of the UK textile market by volume and led by WRAP, a British climate action NGO), reported that its signatory companies had reduced the carbon impact of their textiles by 12% and water by 4% on a per-tonne basis between 2019 and 2022. However, this progress was negated by a 13% increase in the absolute volume of textiles produced and sold. At the end of the day, the increased production rates meant overall water use actually rose by 8% over the period, while the carbon reduction figure stood at just 2%.

These findings from the UK market are likely to hold true in other countries with high GDP and average income, where residents tend to be high consumers*. According to the research by the Hot or Cool Institute (a public interest think tank based in Berlin), Canadians rank 6th among the G20 countries in terms of carbon footprints from fashion consumption, averaging 335 kg of CO2e/capita/year (roughly equivalent to the amount of greenhouse gas emissions avoided by 15 trash bags of waste recycled instead of landfilled).

*A representative sampling of G20 countries as part of the Hot or Cool Institute’s research has also shown, perhaps unsurprisingly, that on average the emissions of the richest 20% were 20 times higher than the emissions of the poorest 20%. This ratio varies substantially across countries, consistent with levels of income inequality.

Translating CO2e into dollar values, the average Canadian household spent around $2,300 on clothing and accessories in 2021; and over $3,000 in 2019. Do you know how much you spent on clothing last year?

How many clothes do (should) you own?

I find it more useful to think concretely in terms of the number of garments we currently buy or own. So, consider this: how many pieces of clothing do you own? You are highly encouraged to pause now and go count it yourself!

No really, count them!

I counted 106 (excluding undergarments and accessories like purses), and it turns out that’s way more than what is recommended as a sufficient amount of clothes.

In a four-season territory, the Hot or Cool Institute recommends a wardrobe size of 85 (including shoes) as the sweet spot to fairly meet everyone's needs whilst preserving a healthy planet.

In the ideal case scenario explored by the Hot or Cool Institute, the average Canadian should aim to reduce their fashion-related carbon footprint by more than 60% in the next 7 years to align their lifestyle with a 1.5°C future*. Globally, researchers concluded that “if no other actions are implemented, such as repairing/mending, washing at lower temperatures, or buying secondhand, purchases of new garments should be limited to an average five items a year for achieving consumption levels in line with the 1.5°C target”. For reference, an average American purchases 68 clothing items per year, while Europeans purchased an average of 42 new garments per person in 2023 - we are talking about a behavioral U-turn across the board.

* Estimates of current average per capita footprints by country were calculated as of 2020 and projected to 2030 by considering expected changes in population and GDP. The per capita footprint target for 2030 is derived from a reduced carbon budget for the fashion industry under the aspirational 1.5°C decarbonization scenario.

Note that this represents an ideal scenario where everyone is allocated an equal and fair share of the global fashion carbon budget. How we can attain this target is a whole different matter, which takes us back to the previously mentioned debates over industry and individual level actions for systemic change.

If no other actions are implemented (e.g. repairing/mending, washing at lower temperatures, or buying secondhand), purchases of new garments should be limited to an average 5 items a year for achieving consumption levels in line with the 1.5°C target.

The “Rule of 5 Challenge” (where someone pledges to limit their fashion purchases to five new items a year) has been gaining traction following the heels of this research. The initiative was recently featured in the Guardian and British Vogue. Closer to home, Unpointcinq (le média de l’action climatique au Québec) also runs the Défi détox vestimentaire annually in March, and recently took us behind the scenes of what it’s like to go on a 1-year fashion detox.

If your garment count is also high, then keep reading – we'll wrap up by whipping through the key lifestyle changes we can make to shrink our wardrobe, lower our carbon footprint over time, and stop wasting money on Fast Fashion.

Buying fewer new clothes, and buying quality when you can: The most impactful and perhaps challenging step, is the mindset and behavioural change towards slowing down our consumption. Here are some pro tips I’ve come across:

Get creative with pairing up new outfits! You can take inspiration from the minimalist movement of a capsule wardrobe. Renaissance’s guide to responsible consumption recommends a ballpark of 40 pieces of garment per season, and provides a reference list of what your autumn-winter wardrobe could look like. You can also change things up by following the 80/20 rule: aim for 80% of your wardrobe to be classic staples, with 20% wildcard options.

Know what you have and when to declutter. Research by WRAP estimates that in the UK, 26% of the average person’s wardrobes have not been worn in the past year. I wonder what the figure will be across Canada? Hoarded clothes are no use to anybody. Renaissance recommends an annual stocktaking of what to keep, what to repair (keep reading part 2 of this article!) and what to sell/donate. I personally love Jennifer Wang’s tips on how to declutter, especially her 3-3-3 rule: Given a particular piece of clothing, can you think of 3 outfits you can wear that item with? Or, can you wear that item 3 out of the 7 days per week? Lastly, can you wear that item 3 out of the 4 seasons? On top of this, learning how to organize your wardrobe also helps you put together outfits more efficiently and minimize hoarding.

If you’re looking for formal wear for special occasions, or just looking to try new looks every once a while, you could explore options like clothes renting/swapping/subscription platforms like Rent the Runway and the Shwap Club.

Within your budget, consider brands with local production and brands that offer repair/maintenance/trade-in services. You could also explore the product range by local tailors and seamstresses, or even learn to make your own clothes! Compared to mass-produced items, you get more freedom to choose quality fabrics, adapt the design to your fit, and support local businesses. You’re also more likely to wear and care for customized items.

Learn to buy quality stuff. Quality has to do with every part of the garment - the fabric, the accessories (like buttons and zippers), the stitches, the cut… Again, I find Jennifer Wang’s pointers super useful.

Taking care of what we have: This could be achieved by several tactics. Firstly, we can all learn to take better care of our clothes (read the care labels, Google wash instructions, and stop shrinking your poor wool sweaters). If you can, try limiting the washes and do it at cool/warm temperatures to save energy, detergent, and water (and your utility bills).

Tapping into repair and alteration are also great ways to make garments fit better and last longer, and that will be the focus for part 2 of this Spotlight Series! At the end of the day, the goal is to get more use out of our clothes, minimize hoarding, and slow down the need to make new purchases.

At a personal level, using clothes for 3 to 9 more months translates into a carbon saving of 8% to 27%.

Buying second-hand when you can: Consider the whole life cycle of a piece of garment (from sourcing the raw materials, manufacturing, distribution through final disposal), around 84% of the carbon emissions occur upstream, that is to say before you make a purchase. Buying second-hand clothes has slowly become mainstream, and Montreal certainly has a great thrift/vintage shopping scene (check out this great second-hand shopping guide for Montreal among other major Canadian cities, compiled by Fashion Takes Action)! When you buy used clothes, you are basically extending their lifetime and getting more value out of the resources and emissions spent to make them.

Responsibly disposing: Textile waste is notoriously difficult to manage, and the wave of low-quality, poorly constructed, and mixed-blend textiles is exacerbating the problem. In Canada, an estimated 750 thousand tonnes of textile waste were generated by consumers in 2022, equivalent to 37 kg per habitant. Only about a quarter of those are collected for diversion away from landfills or incinerators, and an even slimmer fraction (16% of the collected) is ultimately sold for reuse in Canada. The rest are exported to countries with very limited infrastructure to handle this overflow.

The Quebec textile waste management system is faced with a similar challenge: nearly 270 thousand tonnes of textile waste are generated per year (based on 2015 data), or 40 kg (88lb) per habitant – we are essentially throwing out 2 large suitcases’ worth of unwanted clothing, shoes, accessories, and other textile products every year.

We should also keep in mind that when we do donate clothes or drop them off at designated collection points, it is estimated that 48% of textiles collected from Quebec households end up being destroyed. These odds are pretty grim – what can we do to ease the pressure on the waste textile system and give our clothes the best shot at finding a second life? The answer is, all of the above!

In Part 2 of this Spotlight Series, I’ll focus specifically on Repair as a multi-tasking tactic: repairing/altering what we already own gives us more outfit options, helps to delay the need to purchase new or replacement items, and improves the chance of clothes swapping or resale (whether listed by ourselves on Facebook Marketplace/Kijiji, through consignment stores or by resellers like charities) when we decide to part ways with them.

In short, the more textiles we can keep in use here at home, the better. If you don’t know much about the possibilities of clothing repair, or if you don’t know where to find a creative and reliable sewist - stay tuned for Part 2 of the Spotlight Series!

Comments